Welcome to track 2 of my mini memoir ‘Millionaire mixed tape’. You can rewind to track 1 here.

Everything had been pretty rosy up until 11 Feb 1991 - my 15th birthday.

I lived in a chocolate box village, literally in a chocolate shop, in fact. It hadn’t always sold chocolates though. It started off as a Dairy, Wool and Drapery shop selling milk, yarn and flip flops to locals and tourists. My parents had taken over from my mum’s parents, so we were a family of shopkeepers, for a while at least.

One night, around 1983, my mum went to a chocolate making evening class, and it was this that inspired them both to knock the dairy, wool and drapery nonsense on its head and transform the shop into something they called a handmade chocolate parlour. Together they would make their own chocolates, fudge and ice cream, and crucially, create a more effective way of getting tourists to part with their cash.

Now, of course, these kinds of artsy enterprises are ten a penny. Homemade soap, hand poured candles and small batch beers regularly clog up our instagram feeds, high streets, farmers’ markets and even supermarket shelves. All boldly priced at at least five times the cost of regular soap, candles and beer, simply by virtue of the fact that they’ve been made by someone in a leather apron, probably with a hipster beard and a range of instantly regrettable tribal tattoos.

Why do posh people fall over themselves to fork out for this stuff?

Because authenticity; middle class folk long to be deep and meaningful but simply can’t be arsed don’t have the time or aptitude. I mean why go to all the bother of fermenting your own dough / throwing your own pots / maintaining your own garden, when you can buy a pair of jeans that have been run over, shot at and smeared with fake mud to make it look as if you’ve done all those things before 9am, when really all you’ve managed is to get up, switch the De'Longhi on and drive to the office?

However, I digress. Handmade chocolates: back in the 80s this kind of hand crafted, quality-over-quantity product wasn’t as cliched as it is now. Neither was the heavily themed approach of the chocolate shop itself.

My dad - highly creative from birth - had only just exited the swinging 60s and the psychedelic 70s and I think the drugs were still swilling round his system at this point. His idea was to create a concept album version of a shop. A Sergeant Pepper.

Beaulieu Chocolate Parlour took direct inspiration from the approach made popular by Betty’s tea rooms in Harrogate where the waitresses are dressed as if they’ve just stepped out of the scullery (Get the scullery look). Our shop assistants were also attired in Victorian dresses with mutton leg sleeves and white frilly aprons - just a slightly happier, more 80s version of this.

The shop played classical music, had a realistic looking coal fire and even employed child labour if you counted me and my brother. All in all, it was truly something Dickens himself would have been very happy to sup ale in.

It became a success, and not just with the tourists. My dad had his sights on something bigger, so my resourceful and equally hardworking mum would get the Yellow Pages out and ring all the main shops until she got him meetings with big department stores. Somehow he got orders from them all. I say ‘somehow’ because he went to a meeting with Harrods wearing a yellow and orange tie I’d knitted him carrying the chocolate samples in a brown cardboard box with TAMPAX written on it. Anyway, it worked, and from this little shop, with the chocolate factory at the back, orders were being sent out to Harrods, Liberties and Fortnum & Masons among others.

Soon journalists were writing articles on us, we were on South Today, the local news programme. More orders came in, more scullery maids were recruited, and bigger and better chocolate machines were installed.

Momentum was gathering.

Better presents

It was an incredibly exciting time for me, my brother and our little close-knit family because our lives were intricately intertwined with the success of the business. Unlike my friends, whose fathers - and sometimes mothers - disappeared somewhere else to do their work, all of us were fully immersed in the day-to-day rhythms of the shop. We lived above it, worked in it (when I wasn’t at school, of course), and felt every high and low.

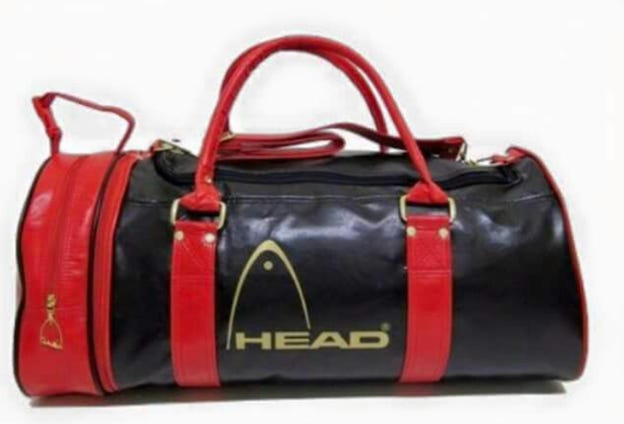

When a long, hot summer brought throngs of shoppers through the doors, it directly impacted our lifestyle. We would go out for meals and get better birthday presents. By the mid 80s we even had membership to the local country club - and a full suite of tennis rackets, tennis outfits and individual Head Bags to go with it.

Bustling summers led to bumper Christmases, hectic Valentine’s Days, and frantic Easters and soon there was no room for us in the flat above the shop, which was being taken over by boxes of chocolates ready for dispatch.

So we moved into a new-build that my dad co-designed, ensuring we had all mod cons. For me this meant a ‘vanity unit’ - a sink in my actual bedroom. My mum got a dishwasher, a bread maker and a Ken Hom1 wok. We had popcorn makers, ice-cream makers, hi-fi separates and a collection of Compact Discs.

Our sofa was from Harrods, my school shoes were from Selfridges, and at 11 I had a Burberry trench coat. By 1988, my brother and I were at private school, we had two cars and a pedigree dog and cat.

It was heady, exciting, and all very conspicuous - which was apt for the times. Greed was good and my parents were very keen on showing that they were making a success of themselves. There was no thought given to preserving any of this money or safeguarding it. The feeling was we were on the up, going places, we were in the grip of Thatcher’s boom - and people needed to know.

And people did know. By 1989 we’d opened an additional shop in nearby Southampton and invited the great and the good to the opening.

Okay, it might not have been Anita and Gordon Roddick of the Body Shop - but that didn’t make it any less thrilling. Or less upsetting for us when it all crashed.

Thank you for reading! Please feel free to click the heart if you liked it. Track 3 will be out next week in all good record shops. We’ll cover the BBC soap Howards’ Way, along with a lesson in 80s economics.

Chinese-American cook Ken Hom sprang to fame in the early 1980s with a TV series on the BBC called Ken Hom’s Chinese Cookery. Ken invented the flat-bottomed wok specially so we could do our own stir fries.

Loved track 1. Loved track 2. Faith, I'm in it for the whole album. Thank you!

I can't believe I have known you for 12 years and only just learning all of this about you. Beautiful and addictive writing as always.