Welcome to track 3 of my mini memoir ‘Millionaire mixed tape’. Feel free to rewind to tracks 1 and 2 to catch up.

By the end of the 1980s the UK was tightly in the grip of Thatcher’s Britain.

Cue synth-pop soundtrack and fast-cut visuals of men in boxy suits striding through Paternoster Square with brick-sized phones, women with tight perms in wine bars, and pink-faced bankers sweating champagne and wads of cash.

“You’ve got the brains, I’ve got the brawn, let’s make lots of money.”

It’s hard to picture if you weren’t there. But for many people, the 80s really were as glitzy, frantic and exhilarating as they look on these documentary programmes. If you lived in the south of England, that is. It was years later that I would learn that it wasn’t quite the same in the north.

The miners’ strike, unemployment, and social unrest were all completely unknown to me at the time - Arthur Scargill was just an irritating man with disgusting sideburns who got in the way of Wogan. (And Ghost Town by The Specials was just a really nice song.)

But in the chocolate box village of Beaulieu in Hampshire, which was only an hour or so south of London, you could feel the throb of excitement pulsing directly from the city.

It wasn’t just its location. Beaulieu was a unique combination of very old and very new. It was sandwiched between the New Forest - Henry VIII’s favourite hunting ground - and the Solent with its renowned marina. So you had honey-coloured thatched cottages, free-roaming ponies and the ruins of an 800-year old monks’ Abbey on one side…

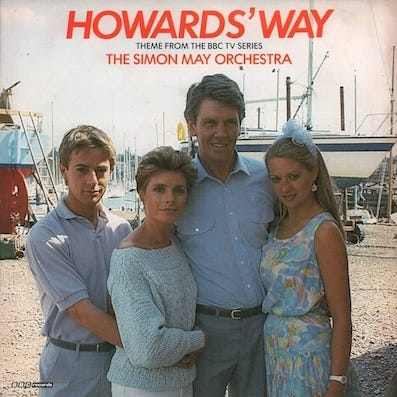

… And super-yachts, sailing clubs, and hit BBC drama Howard’s Way1 (literally) on the other.

As such the village was catnip to rich and - sometimes famous - Londoners looking to escape the Big Smoke. A guitarist from Dire Straits lived up the road from my grandad, Boy George’s next door neighbour moved in opposite us to get away from the paparazzi, and a cameraman who’d just finished filming Superman moved his family down with him for some peace.

You never knew who would turn up at Brownies.

Economics lesson interlude

Beaulieu had always been wealthy, but in the 80s it wasn’t just the old money and sailing elite who had cash to burn - everyone did. It hadn’t always been this way though.

When Margaret Thatcher took office in May 1979, the UK was in turmoil. Inflation was rampant, unemployment was rising, and the country was reeling from the 'Winter of Discontent,' which sounds like a novel by one of the Bronte sisters, but was in fact a period of strikes and social unrest.

Thatcher and her Chancellor, Nigella Lawson’s dad Nigel, quickly introduced bold and unprecedented measures to revive the economy: raising interest rates to control inflation, cutting public spending, and slashing taxes to stimulate growth.

As the proud daughter of a grocer, Thatcher also championed small businesses, making it easier for entrepreneurs like my dad to elevate their ambitions.

Suddenly normal people felt filthy rich

The tax cuts boosted disposable income, while deregulation of the financial sector, epitomised by the Big Bang of 1986, made borrowing easier. Credit cards were now available to almost anyone - they were your ‘flexible friend’ which made spending seem cutesy. Retailers were falling over themselves to offer products ‘on tick’ - consumer spending tripled in the 1980s2.

Getting a mortgage was much easier too, and this ignited a housing market boom, with property values skyrocketing. This surge made homeowners feel wealthier, which encouraged them to spend more on luxury items and status symbols - and there was no shortage of those about. Big cars, designer fashion, tech gadgets and the latest home entertainment allowed people to showcase their wealth and enjoy luxury experiences.

It wasn’t just Harry Enfield’s ‘Loadsamoney’ character that was emblematic of this ability for ordinary people to feel prosperous and successful; it was also the nouveau riche couple who like to tell people in their thick backcountry accents: “We are considerably richer than yoooow”.

Andy McSmith’s excellent book No Such Thing as Society captures the frenzy of these times. “There was an unprecedented amount of money passing through customers’ pockets in these boom years,” he says, “but the question was always how to lay hands on more of it, as soon as possible.”

This taught combination of speculative borrowing, reckless lending, and inflated asset prices was, of course, a ticking time bomb. The bubble was destined to burst.

Last economics lesson of the term

In an effort to control rampant inflation the Bank of England raised interest rates - hitting 7.5% in 1988 before doubling to 14% the following year - imagine that. Many people could no longer afford their monthly mortgage repayments, house prices crashed, and thousands were trapped in negative equity. By 1991, 75,500 homes had been repossessed, up from just 4,870 a decade earlier3.

The disposable income that had fuelled the economy evaporated almost overnight, which meant luxuries like expensive handmade chocolates quickly became unaffordable indulgences. Beaulieu Chocolate Parlour, built on Thatcher's entrepreneurial dream, was in the eye of the storm. The slump in trade left our two shops empty and the tills quiet. The money my dad had borrowed to pursue his ambitions now became an unbearable burden under the crushing weight of skyrocketing interest rates.

The brand-new factory he’d recently had built sat empty and the army of expensive chocolate machines fell silent. The scullery maids had to be ‘let go’ as the orders dried up. Beaulieu Chocolate Parlour, like many businesses, eventually sank under the weight of debt, expectation, and misplaced optimism.

Hubris

A few years earlier, we’d been a source of pride and respect in the village, but that quickly turned to judgment. There was an unmistakable feeling of hubris emanating from the thatched cottages of Beaulieu. We were given a very wide berth and pitying looks, as if what happened to us might be catching.

It wasn’t just us of course. I became good at spotting others like my parents who’d risked it all and failed. You could see them frantically trying to start again from what little they had left. They were still wearing the same lavish clothes (they were never repossessed) but the cars they were driving were now old bangers.

Why didn’t they just take jobs? Because none of them had qualifications; they’d bypassed all that in favour of the fast-track to success, spurred on by the belief that hard work and a bit of risk-taking were all that was needed to make it big. Now, like my parents, they found themselves ill-equipped to navigate the traditional jobs market and had little to fall back on.

It was felt stark and dramatic to me - much more so than the recessions I would live through later as an adult. It was as if all the money had literally disappeared - shops were boarded up and work on building sites stopped mid-construction. Half-finished developments stood as monuments to overconfidence. The south of England felt to me like a modern-day Pompeii - the vibrant pulse of life that once hummed against the sound of Duran Duran’s shiny gold saxophones and the popping of champagne corks had been replaced by empty streets, deserted workplaces, and sad songs with black and white videos.

By 1990 there was a haunting sense that everything had been left unfinished in the rush to get out of one decade and into another. But the next decade wasn’t going to get much brighter for us. It was actually going to get worse.

Thank you for reading! Please feel free to click the heart if you liked it. Track 4 will be out next week in all good record shops. We’ll cover the 1990s, so gather your bucket hats. I haven’t mentioned Five Star in this one, apart from the heading, but I’m going to be issuing a B-side that will cover them.

Howards' Way was a hit soap that launched in 1985 - the same year as EastEnders - and focused on the lives of wealthy yachties living in the fictional town of Tarrant on the south coast of England. It was filmed on the Solent near where I lived, which just added to the glamour.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-22064354

https://ticfinance.co.uk/stats/

This is so good to read!👍👍👍

But it's also quite vulnerable on some level, so thank you for your willingness to highlight this defining era of British history and economics within such a personal context.

Apparently, Thatcher herself was uneasy about the credit boom, and never actually had a credit card.

I suppose maybe, in the end, she allowed it to happen as people are more likely to vote for you if they have more money in their pockets (even if it isn't really theirs).